Previous stop - Kłodawa Next stop - Pinsk

Third & fourth stops - Żołynia & Jarosław, Poland home of the Blooms & Weichselbaums

Malka Molly Weichselbaum Bloom

Based on the birth records of her sons, Dawid (1881) and Hersch (Harry) (1884), in Jarosław we know that my great grandmother, Molly (Malka Weichselbaum) Bloom, was born in Żołynia. We also know that their third son, Chaskel (Oscar), was born in 1885 and that they immigrated to New York City before my grandfather Charles was born in 1889. Two other children, Sarah and Louis were born in New York City in 1891 and 1895.

Uncle Harry told me the family was from Jarosław.

Documents from my research can be seen here.

Our next stop was to Żołynia, a village outside of Jarosław, a city in southern Poland. When my great grandparents, Samuel and Molly Bloom lived there it was part of the Austro Hungarian Empire; the region was called Galicia and its inhabitants Galitzianers.

We knew that our trip would be a lot more fruitful if we had someone with us who could speak Polish. Susan asked Monika if she knew someone who could come with us; Susan is an international expert on transgender history and we figured that a graduate student might be interested in spending a few days with her. Monika asked a colleague, Agata, who recommended Sławomir, a graphic design graduate student writing his thesis on the development of gay "camp" aesthetics in Poland.

We picked up Sławomir, a slight, dark-haired 20-something, at the Warsaw train station in our rented car and began our journey. We soon learned that on the train to Warsaw from Łodz, where he was living, he had been asked by two men sitting near him where he was from. He replied, “Poland.” They said, in a somewhat menacing way, that he didn’t look or sound like he was from Poland. He was successful in brushing them off without provoking them to more aggression. Unfortunately, he told us that this had happened a number of times since the right-wing Law and Justice Party had come to power and stirred up hostility towards immigrants and refugees, which he was perceived to be because of his complexion and regional accent.

After five hours of riding through lush fields, rolling hills and forests, we came to Jarosław.

The next morning I took out the map of Żołynia, which I had been pronouncing “Zoly-nee-ya,” on which I had marked the location of the Jewish cemetery. Sławomir looked over my shoulder and exclaimed, “Oh, you want to go to “Zha-ween-ya!” [pronouncing the “Ż“ like the “g” in “mirage” and the "ł” as a “w”] "That’s the hometown of my grandparents!” How impossibly unlikely was it that the family of our translator/guide, the student of a colleague of a colleague of my partner, was from the same small place as my family? I was utterly floored!

Driving to Jarosław. Photo by Oscar C. Klausner

Anyway, we took off and soon arrived at the town of 5100 people and immediately started searching for the Jewish cemetery. We knew that it was on an unnamed street off the main road into town, Route 877 or Mickiewicza Street. Making my best guess, we pulled over and left our car in the parking area of an automotive shop about six or seven blocks from the town square. I took off into a field, scrambling over the dense underbrush. I was thinking, "here we go, off on a wild goose chase in the baking sun." Soon Susan and Oscar called me back and suggested we follow a rutted dirt road to the left of the field.

Soon we came to a dirt road where we encountered a man on a ladder working on a half-constructed house. Sławomir told him we were looking for the old Jewish cemetery. He climbed down from the ladder and motioned for us to follow him. We walked further down the dirt road which paralleled Mickiewicza Street, heading back towards town.

Soon, on our left, we saw it. Sadness and joy immediately filled my body and tears started rolling down my face. Here was an undeniable physical connection to my deep past. That I was connecting with a place of death -- which, besides birth, is the one thing that all humans have in common -- felt very profound. My thoughts and emotions were with my father, Robert Klausner, who had died only three months earlier at the end of March.

Walking down dirt road to cemetery

Oscar placing stones on the memorial to Sabine Waldman and others buried here

Cemetery from dirt road

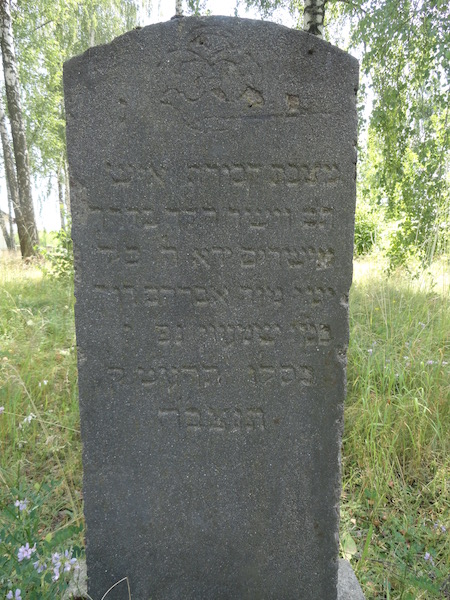

The cemetery felt peaceful. In the 1880s when the Blooms left Żołynia, last names were not used on headstones. Instead, a person’s identity was typically given as “Batya daughter of Chana.” I knew I wasn’t going to be able to find stones for my family because I didn’t know the first names of family left behind and I don’t read Hebrew.

But I felt compelled to photograph as many stones as I could. Great forces have tried to erase my people and I was going to do what I could to make permanent the traces that remain -- notwithstanding the precarious nature of digital photography! Perhaps someone will find this website and happen to see here the stone of an ancestor. Please scroll through the images below.

The website Żołynia Memorial has information about the cemetery which I use here in edited form:

During WWII, the Germans ordered the bodies of some executed Christian Poles to be buried in the Jewish cemetery. This was a common practice in occupied Poland, the Germans seeing this as a final punishment and a deterrent to others. After the German retreat, bodies of Christians in the Jewish cemetery were reinterred in the church cemetery.

By the end of the occupation, the Germans ordered the Jewish cemetery tombstones to be uprooted, and, like thousands of other headstones (or matzevos), they were used as hard beds in road repair and fortification projects. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989, ownership of former Jewish communal property in Poland was passed from the the national government to local Gmina governments.

Jozef Waldman, a resident of Dusseldorf, Germany, whose mother, Sabine, was buried in Żołynia, reached an understanding with officials of the Gmina to allow him to fund a cleanup of at least part of the former cemetery area. By 1991, the field had been cleared of debris, smoothed and surrounded by a new iron and brick fence. Pieces of twenty-three headstones found in the cemetery were mounted on small pedestals as a symbolic memorial. A memorial to his mother and the others buried there was built. Until his death in 2002, Waldman provided funds to keep the cemetery mowed and free of debris. Since his death, the Gmina has arranged for maintenance.

We decided to walk the few blocks back to town to see if the town offices held any records about my family. We soon learned that they only keep records locally for 100 years so further research in the archives would have to wait for another trip or be done via email.

Żołynia town square.

Feeling overwhelmed looking at ledgers filled with information about Żołynia's Jewish residents, which was kept separately from the Christians. I imagine there was no inter-marriage which would have screwed up their system...

On the way out of town I photographed the unnamed road that provides the quickest and most direct route to the cemetery so that others can have an easier time finding it than we did. It's the first left after Smolarska Road going southwest from the town center on Route 277 at highway marker 8.

Unnamed road leading to cemetery.

Close-up of road marker.

Since Sławomir’s family lives just two towns down the road we decided to make a quick visit to see them. Driving past a house that had once belonged to Sławomir's grandmother and in which his mother had been born, Sławomir noticed that his uncle was working in the back garden, so we stopped to say hello. His grandmother had been forced to move (and given a brand new house by the government) in the early 1980s, because the power lines visible in the background were being constructed, and her house was too close. The power lines were built to bring power to eastern Poland from the Chernobyl nuclear generating station, just across the border in Ukraine. The lines carried electricity for only one year before the Chernobyl disaster struck. Because Ukraine no longer had surplus energy to export, the lines were not used anymore, so Sławomir's grandmother had been displaced for nothing.

When we reached Sławomir's apartment, his mother graciously welcomed us, serving us delicious cookies and borscht. It was a real treat for us to meet her and Sławomir's sister. Unfortunately, we could only stay a short while before heading back to Jarosław.

Other sites about Żołynia

- International Jewish Cemetery Project (although it says a key is needed for cemetery, there did not appear to be a lock on the gate when we were there

- Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland, Volume III - Chapter on Żołynia

- Jewish Families from Żołynia

- Virtual Shtetl

- Selection from Jewish Space in Contemporary Poland, edited by Erica T Lehrer, Michael Meng

On our way back to Jarosław we decided to look for the Jewish cemetery. The International Jewish Cemetery Project website says that the cemetery is on Kruhel Pełkińskiej street. However, we could find no cemetery there. Using Google maps Sławomir found a Jewish cemetery off in another direction and we decided to go there instead. That led us down a small, winding, deeply rutted dirt road past farm houses. Our rental car was definitely not suited to this adventure. We kept going further and further and everyone except Sławomir seemed to think we were going off on a wild goose chase. Finally, we came to a fork in the road and Sławomir insisted we go left. The narrow, practically nonexistent road seemed to dead end ahead. We backed out to the fork again and reconnoitered before deciding, at Sławomir's insistence, to go back down to the end of the left fork once more. We stopped the car at the dead end and got out. Menacing dogs were barking from behind a chain link fence. We saw nothing that resembled a cemetery.

The house with barking dogs.

Looking up the hill into the forest.

Finally, deciding that the dogs were really going to stay in their fenced area I started to walk up the hill towards the forest. Sławomir had said that as a child he and his sister climbed hills around his house and found a Jewish cemetery. Was it possible that Jews chose hillsides on which to bury their dead? It wasn’t too long before I saw a chain link fence and some grave stones in the forest! Victory to the persistent! Yay, Sławomir; sorry for doubting you!

The forest is so thick that you can hardly see the cemetery for the trees.

It was so eerie to be in the cemetery in which many stones were toppled over and the others were being crowded out by the forest’s new growth. We could only walk a few feet into the cemetery before the undergrowth was so dense that it made going further impossible. A little afternoon light managed to filter through the trees. The forces of nature were taking what the Nazis left behind. It was very profound to be with death and nature, all intertwined, and my feeling of being one with universal forces and elements deepened. It was like touching the past as I saw the future.

We slowly and silently walked back to the car. This time we took the right fork which soon led us to the paved road. For the record, going south on Route 77 into Jarosław, take a right on to Kruhel Pawłosiowski and follow it to a fork that is near #43. Take the right fork, not the left, (which is Grodziszczanska, the unpaved road that we had driven down). Kruhel Pawłosiowski dead ends in a block or so and the cemetery is on the right.

And I leave you with an image of the ubiquitous storks’ nests that dot the roads in Poland.

Other sites about Jarosław and Zołynia:

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume III

- Virtual Shtetl - Jarosław

- Jarosław - the Hassidic Route

- Zolynia Memorial

- Gasher Galicia - Zołynia